By King Williams

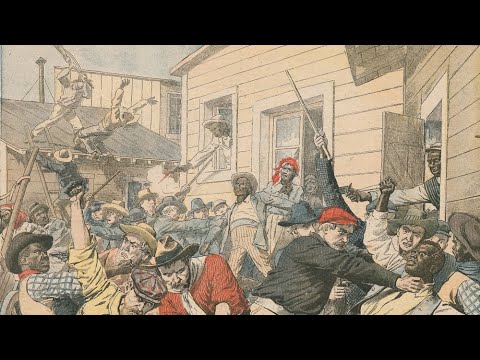

Last month marked the 113th anniversary of the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot. The three-day massacre occurred from Sept. 22-24, and once the flames were extinguished, Atlanta was forever changed.

The city’s geographic boundaries, cultural significance, as well as business and political attitudes and practice have all been influenced by this tragedy, but it’s an event most Atlanta residents know little about.

What was the 1906 Race Riot?

First of all, calling the event a riot is a misrepresentation of what actually happened. This was a coordinated attack against black residents that destroyed numerous homes and businesses, forever altering the city’s physical and cultural landscape.

The massacre was fueled by an ongoing resentment of economic, civil and political gains by blacks in the post-reconstruction era Atlanta. This resentment was aided by fake news and constant radicalized rhetoric coming from the two largest papers in Atlanta at the time, the Atlanta Journal and the Atlanta Constitution.

However, the biggest contributor to this constant barrage of false reports and racial rhetoric of negro-related issues was the 1906 Georgia governor’s race between Hoke Smith, owner of the Atlanta Journal, and Clark Howell editor of the Atlanta Constitution, who both inflamed racial tensions during their campaigns.

This was good for both increasing sales of newspapers and raising the profile of both men running for governor. The problem was there was no real way to prove any of these events ever happened as they were reported.

On Saturday, Sept. 22, 1906, the city reached a boiling point. The papers

were reporting four separate stories of black men raping white women. None of these reports were ever substantiated, but it didn’t matter – the damage was done.

The massacre started in downtown Atlanta on Decatur Street and stretched to Five Points, the West End and finally south into the Carver area of South Atlanta. When it was over, 25 blacks and 2 whites were confirmed dead with hundreds more wounded.

This damaging of black businesses and homes forced the city’s black business district to move north to Auburn Avenue.

It also caused the black residential population to move southward throughout Summerhill into South Atlanta (Carver) and westward surrounding the Atlanta University Center. These in-town population shifts would be the catalyst of decades of migration patterns from within and outside of the city limits.

The 1906 massacre and the response to it were the foundation of what we now know as Atlanta today. The immediate national and international coverage left Atlanta reeling.

As a result, this ‘”Atlanta way of doing things,” pushing societal strife and racial issues emerged as a de facto form of new social, economic and political positioning for Atlanta.

The Atlanta way of doing things…

This positioning of Atlanta more positively among other cities in the south has helped Atlanta continually grow economically in comparison to other cities in the south.

This was due in part to both the national coverage of the event in papers such as the New York Times and international coverage such as Le Petit Journal in Paris. For a city that prided itself then and now being friendly for business, a race riot was a black eye no one wanted

This is still how our city and state runs today, for the most part. And with that, comes a lack of historic-minded preservation or acknowledgment regarding not only the 1906 massacre, but any of our history it seems.

Multiple developments in downtown are currently in the works, from Newport’s development of South Downtown, Georgia State’s development of Auburn Avenue and Summerhill as well as WRS’s re-development of Underground Atlanta. All places that had been touched by the 1906 massacre. All places that currently have no plans to acknowledge the events that happened there.

As we enter into a “new” era of Atlanta, one in which history and place matters less and less, I believe it’s important that we properly recognize an ugly portion of our past. Our history shouldn’t be forgotten, and the developments of ‘new’ Atlanta shouldn’t completely erase one of the most pivotal moments in our history.

This is dedicated to my former professor, the late Cliff Kuhn of Georgia State University. Former head of the coalition to remember the 1906 race riot and one of the most preeminent scholars on the subject.

For more on the 1906 Racial Massacre, please check out the following:

Saporta Report’s coverage in 2013 by Jamil Zainaldin: https://saportareport.com/the-atlanta-race-riot-of-1906-why-it-matters/

Archive Atlanta podcast episode on the topic:

Emory University’s Atlanta Studies:

Electrifying Race Relations: Atlanta’s Streetcars and the 1906 Race Riots

NPR’s program ‘All Things Considered’ 2006 episode for the 100 year anniversary:

The New York Times September 25th, 1906 original article: https://www.nytimes.com/1906/09/25/archives/the-atlanta-riots.html?searchResultPosition=1

And For more on Cliff Kuhn:

Cliff Kuhn’s last entry in the Saporta Report: https://saportareport.com/tell-it-one-more-time-the-history-of-oral-history-in-georgia/

From WABE: http://cp.wabe.org/term/cliff-kuhn

His obituary in the AJC: https://www.ajc.com/news/local-obituaries/clifford-kuhn-historian-was-people-storyteller/blEQJuNxLjARFtYnrmwJyO/

Leave a comment